Painful beauty

Is it possible to remain standing, before the immensity—the desolation—as a witness to what we were, what we still are, and see beauty there? Is it possible to stop time just before everything ends up destroyed? Can we reconstruct a world from its fragments?

Echeverri traces an assumption with landscapes: there is something more outside the canvas, and deep inside, that we aren’t able to define. There is no time there, no action; but there used to be. Behind that apparent stillness, there is a gesture of declaration: at any moment chaos will overflow, a mountain (a report figure can recover its name). Or an evil fabric, another landscape, another even more organic forest, very fine line at the tip of the graphite. Some word that names a destiny. Some cell reflected in itself, meticulous mirror of the empty.

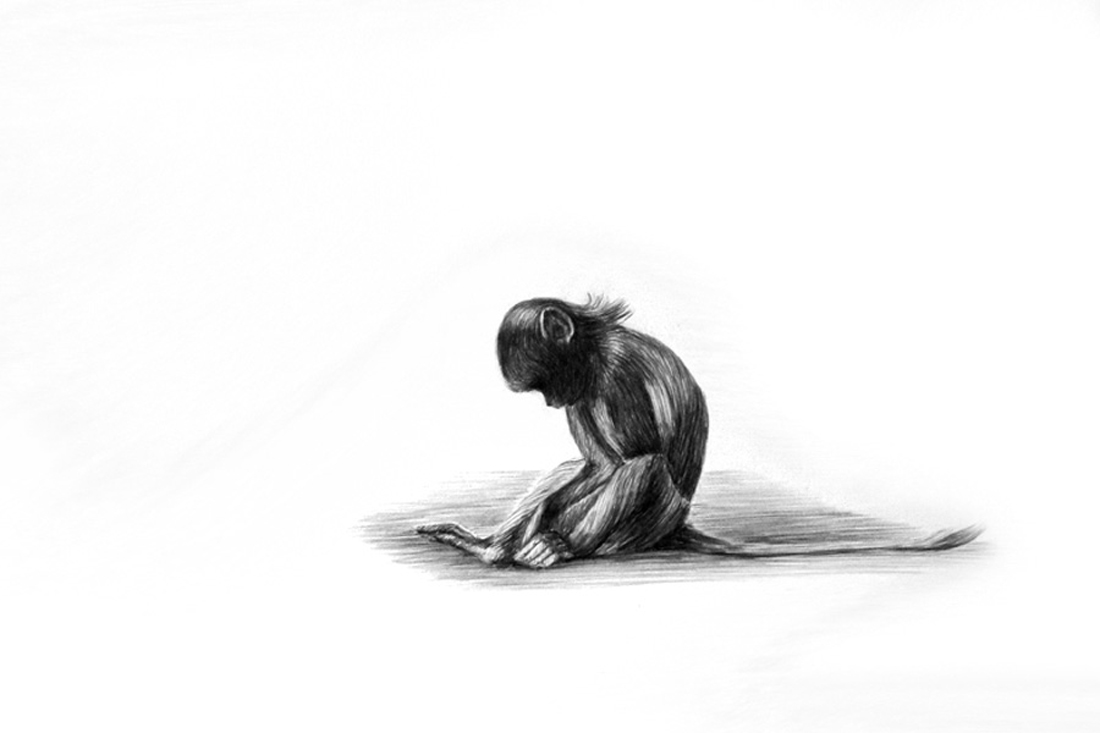

Characters stare at us, making us accomplices, witnesses: they tend to our eye with constancy; they leave the frame in a straight line towards us, or they bring us into it; without realizing it, we are enveloped by them. They live in a plundered world; they see us as if seeing an inexplicable past; they are children that turn their back on the future, they don’t see that forest where there is still something possible. Or they turn their backs on us; they ignore us.

And the Saturnine of soft lines, delicate, stripped of spaces, or in a white space, on Echeverri’s sclera that saw them upon creating them, trapping them in her iris, and later in the iris of those who contemplate them already in existence. Saturnine, delicate introspection. They don’t look at us nor do they give us existence. They look inside themselves, looking for something, an origin. There is no word nor way/path. An internal movement, toward an unknowable world.

Some, then, lost their faces; at one time they had them. Now some have a mask or a beam. Children of the future that cover themselves from the world; Saturnine that hide, sheltered in the curve of their own body. None remember that they have a face. Do we have one still? Or have we drawn one similar to ours to reside behind it, in this world that begins to fall apart? Are we falling apart? Can we be our finished work while the fragments build us? Does the work of Echeverri build us on that side? The vagabond eye—trampland: what we are, broken steps of someone who makes a new silence come to life, its painful beauty.